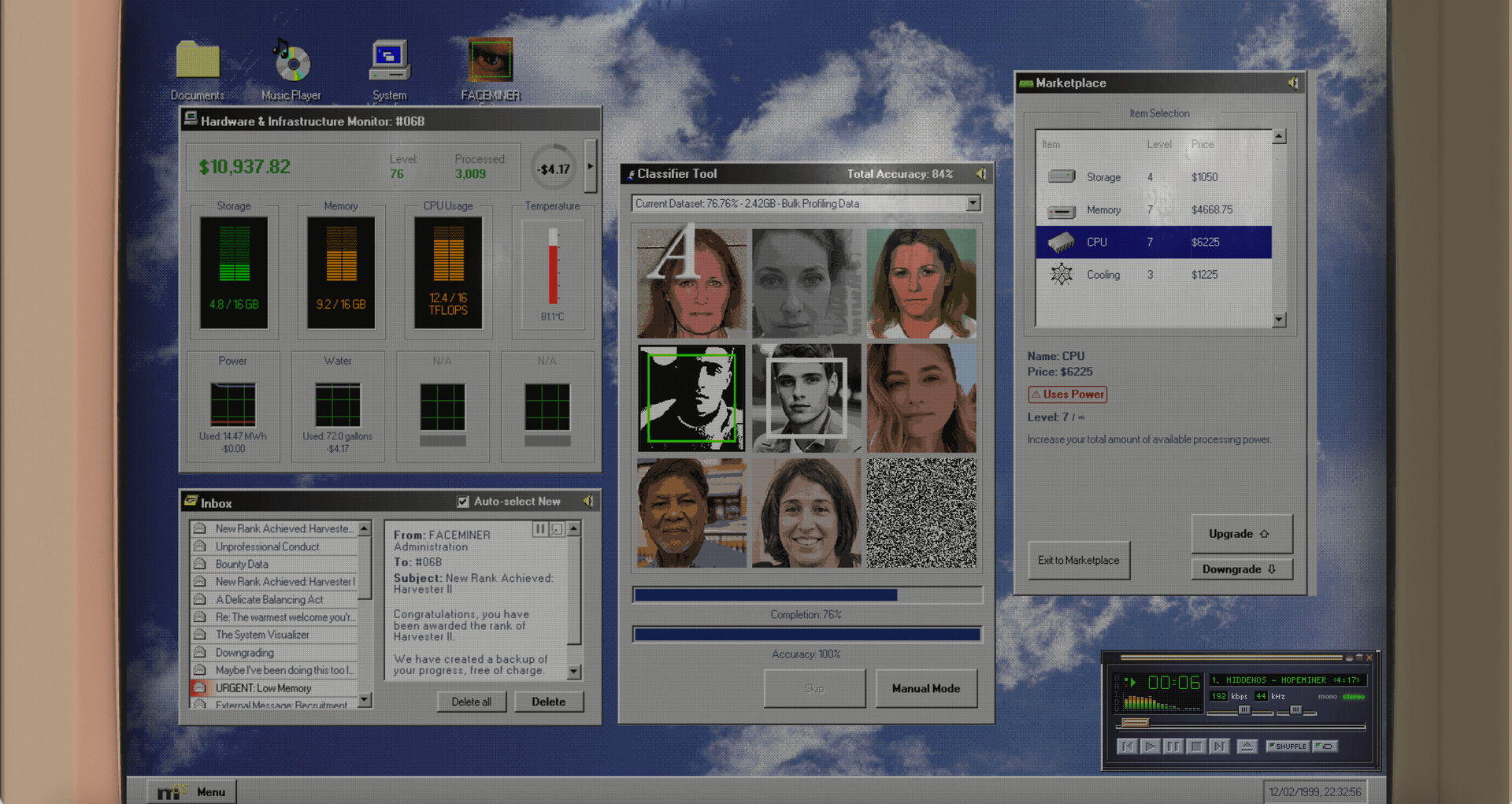

Face Miner is a clicker game in which you are a new remote employee of a mysterious company called “FaceMiner.” Your role is to go through large image datasets and select the images that contain a visible face so that an AI can later train on this annotated data. Like any clicker game, you start by doing the job slowly by hand, and soon you are offered ways to automate the work. You sell your annotated datasets for a profit, you buy software that is able to select images for you, and you upgrade your hardware to handle better versions of this software, etc. The more you “mine faces,” the more money you earn, the better your mining installation becomes, and the faster you are able to process datasets.

In this exponential circle of growth, you have to juggle several parameters: the power of your CPU, the capacity of your storage unit, the temperature of your system, and your energy consumption. The solution to any issue is always to scale up: not enough power? Upgrade your CPU. Too much heat produced? Buy a new cooling system. The energy bill is too high? Install your own generator. The more you progress in the game, the more options you are given to push your mining installation even further. You can deploy surveillance cameras around the world to gather images into your own datasets, and you can distribute your processing power using cluster computing. At one point, the data is processed so fast that the images flashing in the middle of your screen start to merge into a continuous flow. Faces become undifferentiable from one another; it is just a digital amalgamation of what a human might look like. Individuality is completely lost.

Alongside the panels that let you manage all the necessary parameters for the proper functioning of your machine, you have an instant messaging app provided by the company. On this app, you receive communications from the company pushing you to improve your system. Other messages are from your coworkers: some are thrilled about the money they can make mining faces, while others ask for advice on how to manage their installations. At some point, people from outside the company try to reach you, climate activists raising concerns about the energy consumption of FaceMiner and the potential consequences this might have for the climate.

From there, concern about the ecological impact starts to grow continuously. Messages from activists become progressively more frequent and more alarmist, some of your coworkers start to question their activity, and the company multiplies its communiqués, assuring you that the work you do has zero negative impact on the climate and that you should absolutely continue to develop your activity. Later in the game, this concern about climate change enters the game mechanics: you have to invest in negative carbon emission funds if you do not want to pay taxes on your carbon emissions. The game does a very good job of showing how useless and hypocritical these kinds of practices can be. From the player’s perspective, these investments are just new parameters to manage, and they barely slow you down in the pursuit of infinite and exponential growth.

Toward the end of the game, climate activists start to beg you to stop your activity, some even hacking into your PC to display images of burning forests and other natural catastrophes, hoping this will get you to stop. The last parameter that appears on your control board is the global temperature of the Earth, which slowly keeps rising. At the very end, it becomes apocalyptic. Some of your coworkers start to see fires outside, and the company advises you to tape your windows shut and not breathe the air from outside. Images of catastrophes multiply on your screen until you can no longer do anything. It is the end of the game, and of the world.

Despite all these strengths, the experience left me with a slightly frustrating feeling. Face Miner is good, clever, and often effective, but it never fully exploits the potential of its own ideas. The game constantly revolves around mass surveillance and face recognition, yet these themes remain mostly abstract. You mine faces, you process faces, you sell faces, but the consequences of this surveillance are rarely felt directly through the gameplay or the narrative. Visually, the most striking element is the stream of faces flashing at the center of the screen, and it is a shame that this is not pushed further. It would have been fascinating if, among this endless flow, a specific face or character had slowly emerged and started to matter, perhaps appearing again and again, becoming aware, or even interacting with you through the messaging system

The clicker game format is, in theory, the perfect choice to address infinite growth and blind optimization. These games are built on accumulation, abstraction, and exponential escalation, and the point they make is inseparable from their mechanics. Face Miner clearly understands this, but it does not go far enough. The ending, in particular, feels disappointing. Clicker games often lead to absurd, unimaginable conclusions precisely because they push a single logic to its extreme. Here, the final outcome is the destruction of the world due to climate change, which is certainly alarming but also very familiar. As a result, neither climate change nor mass surveillance is treated in a particularly new or surprising way.

This is where the comparison with Universal Paperclips becomes unavoidable. In Universal Paperclips, you are completely absorbed by numbers, optimization, and efficiency. Reality slowly disappears behind spreadsheets and progress bars, and when the consequences finally become clear, they are both absurd and disturbing. Face Miner never quite reaches that level. In the end, the enormous amount of data you process does not really lead anywhere unexpected. What does it actually mean to infinitely mine faces? What happens once every face on Earth has been scanned? Would the system start generating artificial faces just to keep growing? These kinds of absurd questions feel perfectly suited to the game, yet they are never explored.

Overall, Face Miner is still a cool and engaging experience. It is easy to play, its mechanics are effective, and the soundtrack is genuinely great. It succeeds in communicating a general sense of unease and complicity, and it clearly has something to say. But it also feels like a missed opportunity. With the ideas it introduces and the form it chooses, the game could have gone much further into the disturbing, the absurd, and the truly unsettling. I enjoyed playing it, but I could not help wishing it had dared to do more with its concepts.